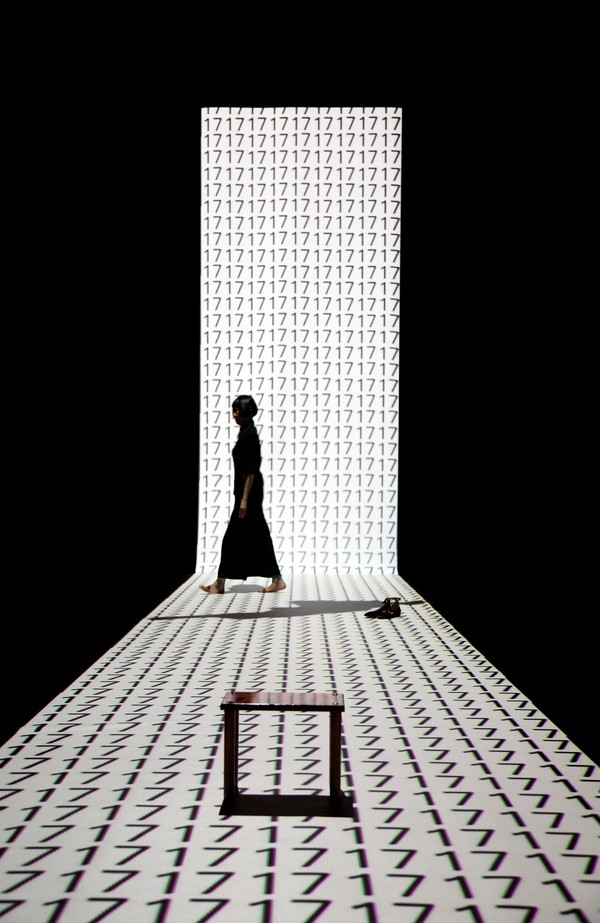

Photo: Pia Johnson

Photo: Pia JohnsonScreen-body-apparatus

This performance of My Self in That Moment begins with a false start. An audience of around thirty people enter a dark space and sit in rows of stools and long cushioned benches. After some time in the darkness, with anticipation building, we are asked to leave the room and told that a technical issue needs resolving. I am not certain whether this was part of the work.

Ten minutes later we shuffle back into the room and our seats. Another pause in the darkness, and then the piece begins. We hear the sound of a voice, or more accurately a voice made up of many voices, a chorus. The voice is coded female (although I question the normativity of my own listening here. Or perhaps it is because I know the performer, Tina Stefanou). It is a mass of voices, with many layers, producing an undulating vibrato effect. My mind drifts to a memory of György Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna, and then, a few moments later to Joan La Barbara’s Sound Paintings. Slippery ambiguity of voices, always moving, yet almost static. Psychologically dissociative.

As we listen, a mise-en-scène emerges from the darkness; a technical apparatus, a screen — or more accurately, a screen made up of many screens, a grid of approximately forty vertically aligned tablets. A distributed image begins to form. It is a woman; seated, expressionless. She begins to slowly move. As the fgure animates, her screen-body becomes misaligned, discontinuous, fragmented, out of sync with itself.

Now it begins to disappear. Blocks of the image collapse into black, darkness. The screen-body-apparutus is being dismantled piece by piece, and another image-body, that of the performer, is revealing itself, iteratively, through gaps in the structure. In this interplay between performer and mediated reproduction I am reminded of Guy Sherwin’s canonical expanded-cinema performance Man with Mirror (1976-2009), in which the artist slowly spins a screen, white on one side and mirrored on the other, while an image of himself performing the same activity is projected towards him. The audience experiences an oscillating visual echo between performance and recording.

In Sherwin’s work, a melancholic temporality emerged over the decades as the performer aged, while his image remained fxed, each performance indexing the irreversibility of time. In My Self in That Moment, we experience a different ‘doubling’, and a different indexing; more immediate and somehow ambiguous, digital rather than analogue. Self and self-image are not contrasted, but inextricably fused, self-as-image. Myself ‘in that moment’, the never-ending digital present, in which we are continually reproduced as images, a spectacle even to ourselves.

All the screens have now been removed. We follow them, and the performer, to another space and a different confguration of materials. The audience now sits in the round, observing a central area in which screen-tablets lie scattered, disordered, image-up, on the foor. Each device is producing images and sounds, creating a diffusion of body parts, zoomed-in details of clothing, images-within-images extracted from context. This scene has a puzzle-like quality, in which relationships between elements are on the cusp of graspable, yet still abstract. The image-sounds are out-of-order, a database waiting to be sorted, sifted for information or clues.

Now the lights go out. In darkness we hear voices and conversations, naturalistic, discussing how bodies and voices become abstracted, and are reconstituted in ways that feel untethered to the bodies that produced them. Electronic treatments, glitches and granulations, begin to intervene; a sonic metaphor for atomisation, fragmentation, and perhaps loss. Yet at the same time signalling the ecstatic proliferation and multiplication of identity and subjectivity. Responding, the performer begins a monstrous choreography. She is adorned in a misshapen, mutant-like costume made seemingly of faces and bodies; a deformed body-made-of-bodies, analogous to the screen-made-of-screens. She screams, as if mourning the loss of a comprehensible relationship to herself.

The screens, now arranged in a circle around the performer, begin strobing in black and white, an impression of self as binary code, subjectivity extrapolated from underlying programmatic logics. The performer vigorously collects the screens, throwing them from the periphery of the stage into the centre, where they pile-up like so much e-waste, in a swarm of screeching tones. Here we see another, fnal, image of the self, constituted as a mound of discarded interfaces, digital detritus. And, the lights come on.

I’m left with a sense of the profound alienation and, indeed, abjection of our mediated worlds. The cascading effect of the self-as-endlessly-reproducing-image plays out as body horror. But the horror is not that of the body’s disappearance, but rather it’s continual reappearance in ever more distorted forms.

Note: This text is a transcript of a voice message dictated by the writer into his mobile phone, in the front seat of his car in the Substation carpark, immediately following the performance. It is an attempt to capture the an immediate response to the work, before second order reflections and the ambiguities of memory take hold.