Photo: Pia Johnson

Photo: Pia JohnsonSounding Digital Consciousness: Robin Fox & Chamber Made’s Diaspora

Robin Fox’s Diaspora (2019) is a hybrid audiovisual event shaped by a “narrative” of sorts that transforms the live electronic music gig or concert format into that of a theatrical experience in a way that might be described as electronic sound theater. In the following essay, fragments from interviews conducted with the project’s lead creator Robin Fox, and co-director/dramaturg Tamara Saulwick, are presented as input and stimuli, in an attempt to grow and develop this notion, or this consciousness, of electronic sound theater, in a manner that is not dissimilar to the coming to consciousness of the entity that is the protagonist in this impressive work.

Origin Stories

It was while experiencing a performance of Diaspora in 2019 that I began to develop this impression that there is an evolving practice of electronic sound theater that might be productively considered as not entirely the same as music theater. As discussed in the Forum introduction, the theatrical outcome of these works is surprising due to the composer-creators’ practices focusing on digital, and frequently non-gestural forms of experimental electronic music and sound art. Fox’s background incorporates both composition (he has a PhD from Monash University) and he has worked as a composer and sound designer for dance; however, considering the nature of his practice, which is intensively electronic, noise-based, and non-figurative, the move to instigating his own complete theater work might seem surprising.

Since the late 1990s, Fox worked extensively on laptop to create live processing systems, including a well-renowned collaboration with Anthony Pateras. He made a significant move towards the visual in the early 2000s via experiments with a cathode-ray oscilloscope,feeding it sculpted noise and projecting the corresponding patterns via live video. This developed into his experiments with lasers. Using a similar process of translating audio voltage to visualized oscillation (and sometimes vice versa), Fox projects the lasers outwards into a smoke-filled auditorium, carving the space into three-dimensional geometric landscapes of tone and noise, in which both sound and image are manifestations of what Fox describes as shared voltage. These projects have become increasingly ambitious, starting with a basic green laser and then moving to the colorful spectacle of RGB. Fox produces works for both standard concert formats and large-scale site-specific performances, such as Aqua Luma (2021), taking place in the Cataract Gorge in Launceston, Tasmania; or Sun Super Night Sky (2020), a laser installation with streamable soundtrack for the Brisbane city skyline.

While Fox’s audiovisual works are presented in electronic music and sound art festivals, he has also worked in theater, particularly as a composer, sound, and lighting designer for contemporary dance works. Very early on in his career he was involved with Chamber Made, then known as Chamber Made Opera.

Fox: The first large work that I made when I was still at university, studying composition, was with Chamber Made. It was a bizarre revisioning of the Narcissus and Echo myth that I wrote for four turntables, double basses, and operatic voices… [Mauricio] Kagel’s Staatstheater really had a big impact on me when I was a student and so these early pieces of mine were very much of that nature. They were based in sound and rooted in sound, but the intent was operatic and theatrical in a kind of oblique way. [46]

When Fox was approached by violinist-composer Erkki Veltheim (then an Associate Artist at Chamber Made) to create a work, he decided to attempt a science fiction opera based on the first chapter of Greg Egan’s novel Diaspora.

Fox: One thing that I’d often joked about with opera is: “Why haven’t we ever had a science fiction opera?” … Once it occurred to me that I wanted to make a science fiction opera, I knew exactly what I wanted it to be—a rendering of the first chapter of Diaspora. … I just loved the description [it gives] of the birth of a digital consciousness—which I had to go to great pains to distinguish from an artificial intelligence. It has this incredible, quasi-mathematical computer “programmery” but also very DNA-driven description of the birth of this life form … It is incredibly evocative and incredibly musical, actually. … [It] suggested all kinds of musicality.

Tamara Saulwick, the co-director, dramaturg, and current artistic director of Chamber Made, makes performance works that are inextricably entwined with sound and sound technologies.

Saulwick: I came into sound surreptitiously. I was working just with recorded voices … documentary materials or first-hand accounts … So first of all, they became useful in terms of constructing content; then, I became increasingly interested in the materiality of sound, the quality of those recorded things, and the detritus within the recordings—and that became part of the language of the work.

I was working on some solo material, and I’d become very interested in this intersection between live and pre-recorded—video and audio, actually. I was really interested in this slippage between the mediated and the live body and voice. Working between recording and liveness is a really fertile space that continues to fascinate me. … I’ve [also] been living with a musician [Peter Knight, currently Artistic Director of the Australian Art Orchestra] for the last twenty years—surrounded by a lot of music, sounds, doing a lot of listening and a lot of talking [about sound]. [47]

Saulwick and Knight have collaborated on several of her solo performance projects, including Pin Drop (2010–14), which uses recorded interviews and foley techniques to explore the role of listening within fear; [48] and Endings (2015–18), with songwriter Paddy Mann, using mobile record players and reel-to-reel devices to create the sound character of the work. [49] Given Fox’s established audiovisual language, Saulwick saw that her role in Diaspora “was to facilitate the work coming into being … trying to support Robin, but also the whole group to make [the work] the most ‘itself.’”

It is also interesting to note the origins and progression of the company Chamber Made. It was formed in 1988 by stage director Douglas Horton to create original chamber opera works. Composer David Young became artistic director in 2009, and grew the reputation of the company by creating intriguing, opera-in-miniature works, often in private houses, site-specific locations, and expanding into new media and digital realms. Tim Stitz took over in 2013 and moved the company to a model that drew on creative input from associate artists, of which Saulwick was one. Saulwick moved into the artistic director role in 2018. In 2017, the “Opera” part of the title was retired to reflect the contemporary focus on interdisciplinary works that explore the relationship between performance, sound, and music.

Composing Consciousness

The sound, structure, and scenography of Diaspora comes from the audiovisual compositional interpretation of the birth of the digital consciousness as described in Egan’s text, but with no narrative-based dialogue. (Several of the pieces involve lyrics but these texts operate as part of the sonic fabric rather than as narration.) Saulwick describes the compositional process:

Saulwick: Erkki and Robin quite literally translated what they saw as this kind of arc of development within the writing. They had musical motifs that had direct correlations to ideas in the text, and it was done in a series of parts. One of the reasons why I think Robin always thought that it would be a good source, is that in many ways the language translates very readily to a compositional format, because [it] talks about building layers and complications of theme.

Fox explains the choice of instruments and palette of the composition:

Fox: I’m fixated with modular synthesizers, so I wanted to make [them] a big [feature of the composition]. [50] I also wanted to use the electronic instruments as props so that the machines are part of the ethos of the work. But I also really wanted to work with musicians … Electronic instruments lend themselves to this kind of automated delivery rather than human gestural delivery. I’ve always had [an] issue with electronic instruments not vibrating. You don’t have the appropriate proprioceptive feedback from a vibrating body. It’s really the sound system that’s your instrument in that sense. It’s not the computer or the software, it’s the speaker that’s the vibrating thing in the room. Working with Erkki, I was going to be working with violin, so I liked the juxtaposition of that. Working with modular synths [but] then also with the most iconic, conservative, orchestral instrument family. The violin is such an iconic reference point for all kinds of music; it encapsulates that high/low culture that we really exploited in the work as well. […]

I wanted to work with great musicians. Madeleine Flynn is a great musician [pianist] and so the ondes Martenot made really good sense there as an electronic instrument that embodied that theremin like quality. [51] Then the idea of having a voice [Georgie Darvidis] … a human voice that would sit alongside the very inhuman construct of a lot of the other aspects of the work. … It did come from this electronic premise, but there was so much of it that wasn’t electronic by design … I wanted performers to be on stage … I didn’t want to do a sound design that supported the theatrical action or even a sound design that supported a sort of visual installation. Tamara and I would often have these dramaturgical conversations where my position would be: “this is a gig”—a gig in this kind of bizarre set. …

There were set pieces, but there was a lot of flexibility in the way [ Diaspora] was played. I wanted to keep that musicality about the work. I think that’s part of my problem with some of these other things that I work on, in contemporary dance, where you have to nail everything down. I deliver the soundtrack in this electronic form, design a sound system and then it’s cued the same way every night. It’s a show and that’s a great way to work, but it’s also not very musical. So I did very much have in my mind that idea of this music-driven theater; the music, and the way we composed the music, was really at the core of each section of the work. …

Even though it did have theatrical or narrative qualities at times, all of the ideas came from the sound and the generation of the sound, and what we were trying to do with the music, not just sonically, but linguistically … to me music is incredibly linguistic … [I mean in] that kind of punch card way that notation has of turning [sound] into a sentence structure and a grammatical structure. You have a form so that then, in the same way you would construct a sentence, you construct a phrase, and then you construct a paragraph. I’m always interested in the intersection points between that kind of linguistic approach to music and then sound as another thing which doesn’t have that linguistic intent.

A key instance within the performance that plays with this musical linguistics is the section that sounds like an interbreeding of a Bach partita and Country and Western hoedown featuring virtuosic performances by Veltheim, Darvidis, and Flynn. For Fox and Veltheim, this piece of very strange composition exemplifies the issue that arises around the cultural context of data that is too easily lost in machine learning:

Fox: The idea behind that was trying to make music that an artificial intelligence (even though we weren’t looking at AI particularly) might make. What would an artificial intelligence make if it could make music and why? And because artificial intelligence is algorithm-based, based on data input it seemed logical that it would analyze a Bach violin partita and then analyze a hoedown and realize that structurally they were almost identical, then just put those two things together, because it doesn’t have any cultural baggage. It doesn’t realize that they actually represent two very different paradigms in terms of music and how we appreciate it as human beings, and in our human cultures. So, I like the idea that in a science fiction world there is no delineation between those … those forms.

In another section, Darvidis sings a version of “Somewhere over the Rainbow” that is digitally diced, spliced, and fragmented almost beyond recognition, yet—for a human audience that understands cultural contexts—resonates with the bittersweet longing to be elsewhere and other. These unfamiliar familiarities are even more curious as they emerge from an extended meditative opening sequence (sustained for over twenty minutes) of undulating sine tones and sub frequencies that—along with the accompanying laser light translations carving the smoke-filled air—render the space thick with affective vibration. Fox talks about wanting to play with the balance of these linguistically music and abstract sonic elements:

Fox: It’s very difficult to present something that’s non-linguistic sonically and have it appreciated without a linguistic lens. I think people still want music and resolution; you know, tonic to dominant resolution—the psychoanalytic safety of all of those structures. … So, I think with this work there are sections where I just wanted it to sit for a while in places that were very strange and not be concerned about where they were going.

For me, this extended opening illustrates how this performance operates on a sonic art sense of time, one that allows for a more ambient and patient extrapolation, rather than musical and theatrical time that often progresses through the accumulation of actions and established moments. I asked Saulwick how she worked with these different time structures:

Saulwick: I think of [Diaspora] as an expanded concert. The opening sequence was a long sustain. I felt like my job was going “Okay, how can we shape the unfolding of visuals—stage lighting and video materials—to meet that tempo?” In terms of the audience experience, it was very physical, like you were in a big bath of sound … [with the] massive subs under the seating, the sine tones were kind of actually waving through you physically. I think that places people in time in a different way. They can really settle into it.

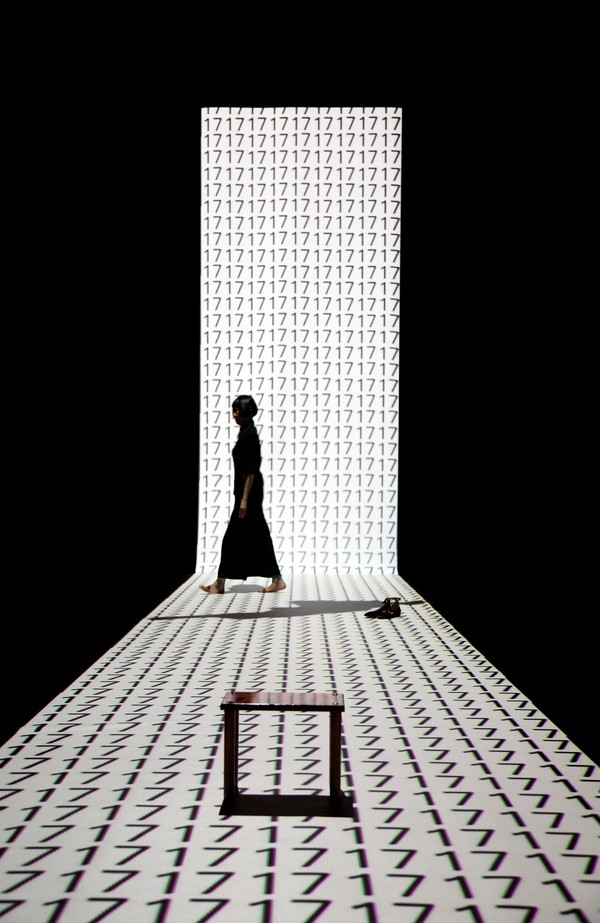

Visualizing Conception

Perhaps what makes Diaspora seem so remarkable as a performance work is the fact that the composition is, from inception, audiovisual. There is never the sense that the visuals are accompanying the sound—they generate each other, converging to activate the space creating the performativity. As well as Fox’s lasers that manifest the full-bodied vibrational sound as three-dimensional wave geometries, exquisite video projections, created by Nick Roux, hang suspended in air, the holographic illusion created by an enormous Pepper’s Ghost. [53] A meteorite emerges out of the depths of the space, making its way towards us. It almost imperceptibly transforms into a brain, an eye, multiple eyes, limbs. Fragmented body parts grow before us, eventually perfectly transposed over the live body of Darvidis, marking the artificial consciousness finding its form.

Saulwick: We had this completely separate development, which was around staging the body in relation to the hologram and what the visual language might start to be. …With the Pepper’s Ghost it becomes a set of pragmatic decisions: how to work with the architecture that the holograph projection surface offers you … There was some level of dramaturgy [around the body] being behind that structure and then revealing the live body at a certain point; breaking through to the foreground space and then being sucked back into the nether space … The live body, the digitized body, and the interrelationship between them.

It could be seen as potentially disappointing that the final digital consciousness takes a human form—is this the anthropocentric limit of our imagination? Will we always try to make our technology in our image? However, this is true to Egan’s text, in which the artificial consciousness has a choice of avatars but is eventually drawn to a human shape gleaned from its library of images. The work’s visual narrative guides us through this process of becoming, making us aware that what is being created is porous, contingent, and includes the potential of so much more.

In the same way that the composition shifts from linguistically musical to sonic, the visual language also shifts between figurative to abstract. The piece concludes with a spectacular explosion of light and sound (referencing the carving of a meteor in Egan’s text), in which Fox’s stadium concert pieces create the template, celebrating the bursting into sentience of this new consciousness. It’s an unabashedly, uncritical, and joyous celebration of a new digital, post-human life. While there may be causes for concern over the consequences of our increased transformation into digital life forms, they are left for others to argue. In Diaspora, the integration of the body within the digital entity attempts a hopeful trajectory that the notion of the corporeal will remain a component of an expanded consciousness. One of the burning issues of digital consciousness construction and substrate mind independence is around how a brain in a vat can sense its environment and replicate the kinesthetic knowledge this generates. In Diaspora, there seems to be the suggestion that corporeality remains significant (even if in some emulated form).