play walk listen yes

The first thing we do is mute ourselves. We are acclimatised to a world lived via Zoom. Silence has become our natural state of being. There is a sense, though, of the gathering of thoughts. Of readiness. In previous years, the Hi-Viz exchange has thrummed with noise: chatter, footsteps, the scraping of chairs—and laughter, the joy of being in the physical presence of like minds, like practices and like experiences. This year, our gathering has the qualities of sound: it is intangible, atomised, and full of potential.

*

Janet Cardiff in Conversation with Tamara Saulwick

Eleven years ago, I fell in love with Janet Cardiff. It was Opera for a Small Room that did it, installed at ACCA. A tiny chipboard shack, filled to the brim with record players. A disembodied voice uttered gruff stage directions as the needles dropped, as if by invisible hands. Shadows passed on the walls. A train rocketed behind us, the lights swinging in the room. A sudden explosion of colour and music. There was a longing to this work, a sense of profound isolation. It was achingly tender, full of sublime beauty and quiet devastation. I think of it often, this year.

Janet flickers onscreen. She is in her ‘play studio,’ in the home she shares with partner and collaborator George Bures Miller. White canted walls are covered in pinned images. Every surface is heavy with stuff. There is an old landline phone. This is the dreaming space. In the big production studio, she says, they are working on a reproduction of Storm Room for a gallery in Denmark.

On the tiny Japanese island of Teshima is the Storm House, an expanded version of the original Storm Room. In 2018, my partner and I caught a plane, a train, a bus, a ferry and an electric bike and stood in front of the wooden building. We only stood in front of it. It was supposed to be open, the day we went. Perhaps we read the pamphlet wrong. I pressed my fingers against the glass and tried to will the installation to come to life. There was no sound but the wind.

The secret language of brief glances and suppressed giggles that usually permeates professional gatherings has moved online, too. A friend messages me: Omg what is Janet's life!!!???!!! We are looking at an image of the front of her studio. Bright blue water. Grass shaking fistfuls of itself at the sky. Behind the clouds, the sun casts nets of light. Today, Janet says, there were two swans. A real sign of winter. She and George saw a bear across the water. Once the ice sets in, she says, they watch coyotes cross the snow. Half a world away, I can feel the collective ache of us all, gazing into that soft, green-blue world. Tam laughs that the Australians will be wanting to storm the place. My friend messages: Shit. I’m moving to Canada.

Janet is discussing the audio walks with which she first rose to prominence. She describes walking through Banff with a tape recorder, speaking notes to herself. At one point, she pressed the wrong button and rewound the tape. Suddenly, she heard her own voice, her private thoughts, her footsteps and her breath. Something in her shifted. Haunted by her own history, she began to make.

We hear a snippet of Her Long Black Hair, designed to be experienced in Central Park in New York. Walking is very calming, Janet’s voice says, flat and warm. One step after another. One foot moving into the future and one in the past... The hard part is staying in the present. This year, we have been walking like never before. Pounding out steps in the hour we are allowed outside our homes. ‘I’m a strong believer in letting your brain go when you walk,’ says Janet. It was Diogenes who allegedly first uttered the phrase: solvitur ambulando. It is solved by walking.

When I first bought a pair of binaural microphones, I walked around a foyer wearing them. When I listened back, huddled in the stairway with my laptop on my knees, the bleed between reality and recording broke down. I looked up to find the laughing woman nearby, but she wasn’t there. She was in the past, the bright tinkle of her laughter getting further and further away with every breath. ‘It raises philosophical questions about how we know reality,’ Janet says, ‘other than through our senses. And the senses can be fooled.’ Through sound, her walks carve rifts in the world. Impossible things become viable. We believe what might be. According to Mark Fisher, the uncanny contains two facets: the weird (that which does not belong) and the eerie (the unsettling quality of absence). Janet Cardiff’s walks function in both modes. They give us auditory presences so real that we cannot doubt that we have shifted to some other space, to some outside zone. ‘It’s like a theatre trick,’ Tam says. ‘Space and time and memory are all in these strange, slippery spaces.’ We turn to hear our companion, and we are alone.

‘What feels important in your practice right now?’, asks Tam. ‘Play,’ says Janet. ‘We’ve been some of the lucky ones. Covid has given us a lot of time to play.’ She turns the camera around to show us the studio. ‘I have a little toy torture area over there where I make things.’ And, almost offhandedly: ‘That’s an animatronic gorilla head.’

*

Small Group Practice Discussion

When the gallery view pops up, there are so many of us. Pages and pages and pages. I scan through the faces, beaming. When Emilie asks us to type in the chat window three things we can hear now, the responses are a kind of concrete poetry, moving so fast it’s almost impossible to read: forklift voices fridge hum traffic bubbling aquarium cutlery my sleeping babe. How we’re feeling today: warm tight expanded grateful foggy emotional quiet warm spacey thoughtful. How the last three months have felt: limbo stasis lost slow fast hungry long challenging clarifying a silent scream elastic heavy soupy sensitive prickly dull foggy hard. There is such a rush of humanity, here, on my lap, in my hands. We are all bubbling away, together. There is a shocking sense of connection, more profound somehow than simply being in a room together. We are reaching out towards something. The three things that are important to our practice speak volumes: listening renewing hope connection time place space sovereignty listening holding space gentleness with myself play play play. In this year of enforced stillness, we are remembering to find joy in our practice. When Emilie unmutes us all, we are a cacaphonic chorus. There are so many smiles.

The shifts from group discussion to breakout rooms never stop being a strange form of teleportation. Sentences are cut off mid-way through, like a hologram coming to the end of its data. We are shy, every time. Missing the nonverbal cues that indicate who is ready to take charge, we watch each other closely. We are brimming with attention. Someone speaks. They describe being midway through a new project and panicking. ‘The panicking was kind of good, though,’ they say. ‘It was a questioning of what was really important, instead of doing, doing, doing.’ Heads nod hard and become blurs of pixels. Yes, we say. ‘You play music, you don’t work music,’ a composer muses. ‘I’ve been working music.’ Yes, yes. Sometimes, in industry events such as these, there is a tint of envy in the room. Competition. People scoping for who’s working where. This year, we aren’t bragging about the work we’re doing. We’re celebrating the tiny joys we’re finding in what is at hand. We have lived long enough in this strange new world that we are finding the delicacy in it. Another participant has been lying under trees and listening. ‘Nature is able to move again, because humans aren’t crashing through. I’m a bit sick of people talking, to be honest.’ Laughter. There is something in all of us, in these conversations. The overly bright eyes and slight tension of voice that one observes in the feverish and grieving. We are raw, somehow. Two video screens light up with smiles: both have been obsessing over Hildegard von Bingen, 11th Century writer, composer, abbess, mystic, natural scientist and healer. Hearing her music in the present, they say, provides a remarkable connection to the past. Between the notes, there is something of her still.

*

Vibrato Virtual by Aviva Endean and Cobie Orger

I am treating my phone like a lover. It feels obscene, to roll it over my face like this. I feel a tinge of fear that the contact between the screen and my chin will worsen my acne outbreak. It feels good, though, too. I treat this object so brusquely. To handle it like an instrument makes it precious again. There is something beautiful even in the introduction to this work: the idea of the audience as a group of massed sound makers. There is something equalising about it; the way the premise flattens the hierarchy between maker and audience. We all perform to ourselves, watching our coloured squares. Earlier today, Janet Cardiff said that the act of watching inhibits the process of listening. I close my eyes for a few moments, feeling the strange buzz from my phone speaker, noting how the pitch shifts with movement. The tingle of sound on my cheek feels like I am shaving, a moment that transports me momentarily into another life that smells of Gillette; a portal that opens and closes in seconds. I watch the audience, my fellow performers. Someone has fallen asleep, her mouth open in a wide O as we open and close our lips over our phones. We all say ‘Wow’ with a voice that is not our own breath. A parent and a child do the work together, serious faces fixed on the screen. I close my eyes again. I graze the tiny hairs on my face with the phone. It feels like the palm of a lover. I almost cry, and then feel ashamed for it. We roll the track again. When we all sing, the audio distorts our voices into pixels: flat and square and tumbling into our speakers and out of our phones and into our mouths and back into air.

*

Audiosketch: conversations with Rainbow Chan and Ros Bandt

This is the point in any conference when the heaviness sets in: post-lunch, heads brimming. The chance to lie on my sofa in the sun and just listen is glorious. There are many things that are unusual about the way that Hi-Viz is run. This is one such thing: the softness of it. The awareness that communion takes effort. This segment is a break and a salve. I lie down and close my eyes and listen to women I like having a conversation. It feels like long days in easy company, the way you can doze while chatter occurs around you. Ros speaks about feeling creatively lonely, about seeking out artistic companionship. She describes good conversations with creative peers as nourishing and expansive. Years ago, a wise friend once told me that all relationships have a sense of movement. Some are expanding. Some contracting. Some have stalled into immobility. To hear someone else’s expansion feels delicious. Rainbow Chan describes herself as a sound: mahjong tiles clacking under the fingertips of middle-aged ladies with lovely manicured fingernails. ‘It’s like brushing against a snare drum,’ she says, and the audio proves it, and I sigh at the rush of noise, like soft rain. In a physical conference, the podcast guests, Rainbow and Ros, would feel distant, pre- recorded. In this digital world, they becomes participants, like all of us. They feel just as live as the conversation between the hosts. I message my friend, whose art and mind feel to me like stepping through a hidden door. I ask her on an art date. She says yes.

*

Group Discussion: Fayen d’Evie and Sonya Holowell

Sonya Holowell describes the words that demand attention from her, or gently but persistently knock. I have several such words: ritual, threshold, tender. When they are spoken or read, they glow. They carry some curious aura. For Sonya, the words that spring out might be problematic, or loaded, or in need of unpacking. They might just be relevant to her, in her current season. This is her phrase, ‘my current season.’ I like this notion. The acknowledgement that one way of being gives way to another, like weather.

In the breakout room, we are bolder. We discuss the word resilience. It is a word we have heard a lot this year in the arts. Like pivot, it suggests an easy reaction to chaos. The woman I have just asked on an art date works with children and adolescents. The psychologists she consults say that while challenges build resilience, there are traumas that are too enormous to be integrated. Some things are just too big. Resilience, too, suggests that what existed before is worth returning to. We are all beginning to ask: what could be better? What can we build in the space where the world came unhinged?

We discuss Fayen’s work with Bryan Phillips; the way that disability and parenting and caring are all things that make isolation stretch out beyond this pandemic. There is a vulnerability in these conversations. We unpack ideas messily, complexly. We are resisting decision-making. One of us confesses that she used to be a grammar Nazi, but that after a traumatic accident, the words she writes come out full of errors. We discuss Fayen’s way of guarding her solitude. We are envious of that. We are envious of that quiet. It feels closer, now, this year. But still, tantalisingly out of reach. One of us describes growing up in a Jewish household where the sabbath was strictly observed.

A day where it is culturally legitimate to have a time to do nothing but sit and think and talk with people. What a gift, she says, to have that legitimised in her life. That beautiful, flowy energy. I recognise this description. It is what I feel when I meditate. It is the difference between loneliness and solitude. It is the space where my brain shuts up and I enter a state of being deeply curious: as though the world is porous and I am both empty and full at the same time.

*

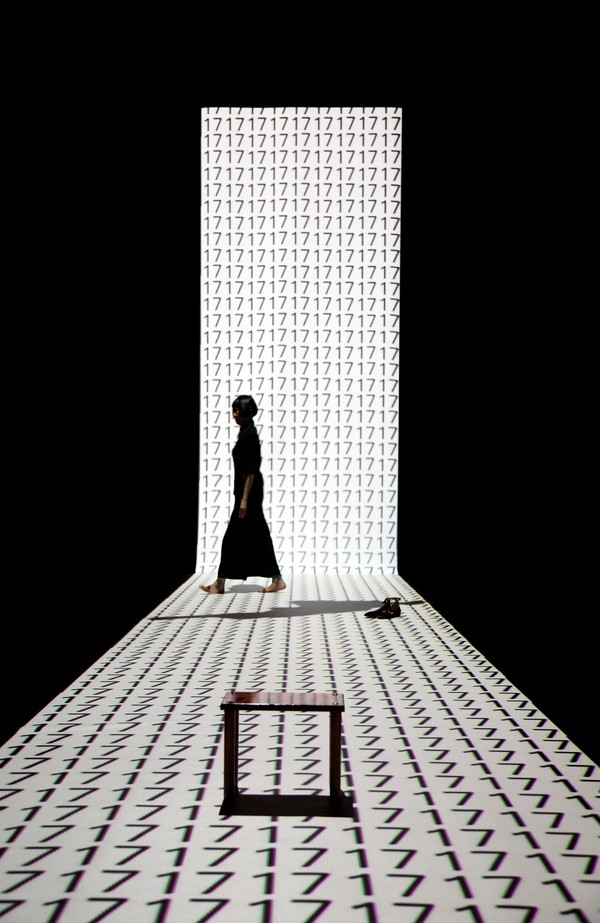

Living Memory by Sui Zhen and Collaborators

Oh god, Sui Zhen’s beautiful teenage self, lanky and cross-legged, saying, ‘I just wanna show my friends who they are.’ I was such a child: precocious, awkward, determined to archive everything. The work unfolds in waves, of alarming doubled selves and purring, wet reptilian synth. It is like an erotic nightmare. It is hypnotic. I can see it installed already: a huge, round room, with the screen on the ceiling. I want to lie on a deep red floor and stare up at this, to surrender to it. My mind is fragmented, this late in the day. This work sucks me in, lulls me into some wide-eyed fugue state. Earlier in the day, Janet Cardiff described the quality of her voice in the audio walks as that of a somnambulist. This video feels like falling face-first into someone else’s dream. It is disorienting and familiar and enticing. This whole day has been full of loops, of themes repeated, of words bouncing around in the ether: play play play walk listen yes hear yes. Past and present and future, and women’s voices, narrating the moment as it slips away, tethering it back to the now, saying what if this was still happening? over and over again.

*

We don’t get to say goodbye, really. There are no promises to call. One or two people type their email address frantically into the chat, but when it’s done, it’s done. We all shatter into digital nothingness, into quiet, into the chambers that echo for ages after you drop a stone in. We go back to lockdown, to our homes across the country and the world, and yet, and yet. We are not alone.