Lexicon of the Unperfectly Heard

Sometime around noon on Day 1 of Hi-Viz Satellites, Punctum Inc. Artistic Director Jude Anderson took the mic and read out some words and phrases which she had found memorable in the talks and moderated conversations. It had been a heady few hours; Zen Teh and Adena Jacobs talking about their modes of making (this year’s theme), followed by audience members candidly catching onto each others’ ideas and expanding them into big stimulating metaphors. Once the panel discussions began, the dialogue never ran out of breath– abstract propositions laced through each other and into my notebook. A collective experience of pensiveness cradled between Bendigo, Singapore and Zoom, with the occasional buffering. Jude’s intermission was a welcome recap of all of it.

The third edition of Hi-Viz brings together live audiences in different locations. When artists practising in different socio political and cultural worlds come into conversation, questions about meaning are pertinent. Are they speaking about the same thing with vocabulary accrued through different contexts? What values and priorities arm these concepts?

A lexicon is an apt way to reflect on the conference. The following is a selection of words that repeatedly wandered into various conversations, and words that might reveal the stakes in some of those thoughts.

1. “Gap”

The gap provided a visual for several ideas articulated over the course of two days.

In her greeting introduction, Chamber Made Artistic Director Tamara Saulwick introduces Hi-Viz Satellites as a response to a gap in the performing arts and sound art arena. The conference was a rare intersection for women, non-binary and gender diverse artists working in various disciplines to meet, talk, and exchange ideas. It was nice to have experienced this exchange in two forms– moderated in and between the different locations, and organically as we got to know each other during the one- hour lunch breaks.

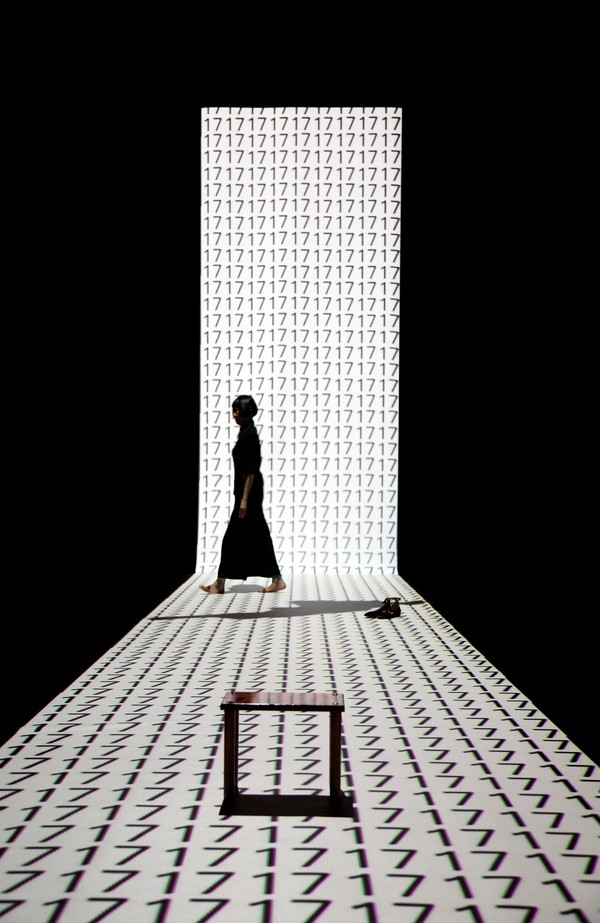

The gap is also used in the context of making. Theatre director Adena Jacobs talks about enjoying an introspective experience when she watches a performance. She aims to create a place of disorientation for herself and for her audience. The gap is a goal in Adena’s work; it is a lapse of logic “beyond the familiar”, a space where her audiences can form their own meanings.

Watching clips from Adena’s production Howling Girls, we see her process of expounding on the political arena of the body. In her tradition of shattering the views and values fed to us in myths and childhood stories, Adena dramatises the trope of female hysteria and the reality experienced by those

in the margin who are not heard or believed. She asks, how does our body respond to catastrophe? What sounds do we feel when the expressing body can’t speak? In the two-minute clip I am haunted by soprano Jane Sheldon’s vocals as they stretch and twist their way into rarely visited crevices of my chest.

While Adena engages in a practice of denaturalising the familiar, Zoom participant Indiya puts forth something quite contrasting: suppose artists make in a language that speaks beyond our artistic community, would they become part of the political conversation in a more meaningful way? Indiya feels that we are losing the audience that needs to hear our insights and ideas. Changing the course of “centuries of history of seeing what’s going on and not being heard”, she proposes looking at art as a research phase and not the final language. I can’t know exactly what she meant, but her words gave me questions. I wonder, and deduce from her reference to political conversation, if she is suggesting that artworks communicate in a way that is approachable to the layperson, so that their ideas may be adopted by many.

Emma, an audience member in Bendigo set an intention: “to stop...this human pace, point to a present, and allow others to walk into a presence”.

Such a space open-ended enough for others to step in– what does that feel like? Is it drawn in a familiar language, or do we dismantle our languages so we can build a new one? It’s a tough spot to touch, but I think art can bridge that gap. Art presents the unspeakable on another level, working with sensations that might feel novel but simultaneously feel like we’d always had them somewhere inside.

2. “How to make sense of things that we don’t include”

First off ...what is it that we don’t include. When the phrase first appeared in an audience member’s question, it was used more in reference to the editing of ideas within the creative process. I’d like to borrow it to articulate a contentious issue discussed in Singapore on the first day– who gets opportunities?

During the lunch break a few of us sat on the floor to eat sushi with Sharon Chang, who had just moderated the Singapore panel. Sharon runs the annual National Arts Council (NAC) art appreciation survey. I was thrilled with the opportunity to pick her brain about government priorities when it comes to supporting the arts. I told her about a curious observation I had getting off the train at a busy stop one evening. We don’t really have a lot of buskers in Singapore– buskers have to get a government-administered licence and I heard the process is not easy. This weekday night, however, I heard live crooning of a Top 40 love song. One minute later as I went down the escalator, I was licked by trails of another voice and a guitar strumming a rendition of another popular romance track, only fooools rush innnnn.

This observation led me to ponder about how public officials conceive of the balance between what people want to make and what people want to hear. Should those in power prioritise giving space to voices that soothe a wide audience, from the stressed out office worker to the teenager that seeks out the flavours of his Tik Tok feed? How do they weigh this mandate of catering to the majority, with that of listening to the handful of voices that have something to say but whose aesthetic value might be more cryptic?

I posed these questions to Sharon. Her reply was immediate: as a government statutory board, NAC had to look out for Singapore’s diverse demographic, and protect people from being confronted with something they might find harmful. Reiterating something she had mentioned during the panel discussion, Sharon contends that creating a common space of growth in a society with so many cultures should be a gentle and gradual process. The others in the circle joined in the discussion. Jum, a theatre arts educator, suggested that if the government did a little less meddling, it could be a strategy to nurture society’s appreciation for the arts. Two arts management students nodded in assent. They brought up how there was a lack of communal spaces where people could gather organically, on their own terms, what online participant Judy earlier described as “spaces where performers and audiences can discover their own agency”. Of course such a place would exist when a whole gamut of other pieces come together into a new sociocultural reality– lower cost of living being one of them– and this place of agency wouldn't be a government-managed resource hub, which does currently exist.

3. “processes that feel like they feed and feedback”.

In Singapore, parties are one of the sources providing necessary collective effervescence that keeps society going. As DJ, producer, and artist Cherry Chan took us through her neverending body of work, resplendent with projection-mapping experiments and parties in a multitude of formats, she communicated how the intention to create always begins with, “how can we have fun (listening and sharing what we want to play)” and “what can we bring to the community?” Her collective Syndicate was born from the excitement among friends to combine visual arts and music on a Friday night dancefloor. Over time the canvas extends beyond the nightclub– projection bombing on an alley wall in London; audiovisual loops on the facade of an iconic hawker centre facade in Singapore, remixed from the visual patterns and sounds of the neighborhood. Parties allow creators like Cherry to take risks among friends. The obvious breeding ground for connection (with each other, with music, with one’s body), parties were a symbiotic nexus emulating something Tamara, sitting in the audience in Bendigo, said she sought in her work as artistic director– “processes that feel like they feed and feedback”.

4. ‘increase the way we identify’

It was striking for me to observe the different ways in which the Australian speakers and people in the room with me in Singapore talked about, addressed, or alluded to cultural memory. I think the difference I felt lay in the subjectivity one subscribed to, within the power dynamics of society.

The Australian speakers started their presentations by acknowledging the unceded land on which they were standing. Because of this I now have heard of Dja Dja Wurrung and the Taungurung Peoples of Kulin Nation. The recognition of cultural contestation goes beyond the customary opening script; it appeared in several speakers’ introduction of themselves and their work. Adena is interested in “how history infects through generation” and strives to unlearn the central values from dominant narratives like the Bible and Greek tragedies. Moderator Amaara Raheem says being invited to facilitate a discussion is a positionality. She situates herself as a dance artist, an immigrant from Sri Lanka, and someone who has just bought a bush block in the Northern Grampians. These multiple belongings to place inform her interest in how movement and language migrate. Lz Dunn is a Scottish English settler living on Dja Dja Warrung land who works in the field of human movement ecology. In her barefoot-listening workshop, Lz asked the live audience in Bendigo to be cognizant of their colonial heritage. As they walked atop objects she had brought in, she reminds them to take note of this moment of intersection and the different pathways that brought them into this gathering.

These customary utterances and the reflection of positionality through one’s practice and self- identification give me a tiny glimpse of the relationship between gender, race, and power in Australia, at least in the arts. They suggest how one perceives insider and outsider, and the norms that fuel these considerations. This article isn’t the place to discuss the ways these relationships and tensions exist in Singapore. I’ll simply recount the contrasting references to identity and heritage, and the questions that came into my mind.

During the panel discussion, Sharon described Singapore as a microcosm of Australia to highlight how people here are also descendents of immigrants from different parts of the world. Sharon’s larger point is that in order to administrating this multiculturalism, civil service makes it a priority to ensure that “the area in which different people can come to talk” can grow over time, gradually and gently. Sharon was addressing a question that Amaara had directed to the Singapore audience. Furthering Indiya’s proposition to “increase the ways we identify”, Amaara asked, what do you think of identity in a queering and interspecies world? (Abstract propositions lacing through each other!)

An educator in the room first took the mic, saying, “I don't think I'll speak directly to the question as there are several things that we know in the education landscape that we don't get into.” He would rather talk about “interstices of spaces” and the importance of openly listening to each other, believing the goal should be dialogue, not a singular vision or outcome. Both Sharon and the educator’s answers seem to approach identity as always emergent, always cognisant of the constraints.

These responses might tow the official civil service line; but they provide an invitation for us to take cover in their robust tone and volume and imagine our own latent interpretations.

Composer Belinda Foo had a two-part presentation in which she talked about making at the intersection of culture and discipline. In a section titled, “Creating at Transcultural Intersections”, she asks the audience, what makes Singapore art Singaporean? No one could give an answer in the form of any aesthetic characteristic. She flashed a slide that said, “acculturation and entraining: diasporic traditions, colonial music traditions and current globalised forms” and played a recording of a piece she had composed called Durian Pantun. We heard an intoxicating baritone sing like it was reciting a prayer call and the strings of a cello, sitar, and erhu shimmer next to each other. It was beautiful and otherworldly, and made the fluorescent light of the room feel a little warmer. While I liked the piece, I wondered about Belinda’s goal of finding a Singaporean sound.

Why does cultural heritage have to be about the main traditional artforms from imagined mother lands? Singapore came about from colonial exploitation, mass migration of people seeking economic betterment in a land already occupied by several cultures; and more recently, heavy-handed social engineering that legitimised a certain definition of survival– what the government and market allow to breathe. There’s a reason we can immediately list out our favourite Singaporean dishes but struggle to identify a Singaporean aesthetic. In trying to reflect “the melting pot”, perhaps it’s more interesting to locate the forces that prop up and suppress different narratives, and the shared cacophony we all experience (relentless cicadas? train doors queefing?).

In any case, this drive to find a Singaporean sound is hinted at with words I heard thrown around quite a lot on the second day, as instinctive asides and within presentation slides: “western” and ”colonial”. “I don’t want to be another western composer”, “I don’t want to follow the Western notion of wellness”, “Everyone, come sit on the floor. Chairs! They’re so colonial.” I haven’t encountered these binaries in a long time. Perhaps they exist in the discourse of the creative realms represented in the room– classical music, alternative wellness culture– spaces I am not acquainted with. The formal presentations allow me to enter these spaces and get to know them on an intimate level– hearing someone talk about their practice, as well as a discursive one– seeing the kind of language they use.

5. Provocation

I was struck by this term coming in and out of the panel discussion– “thank you for the provocation”, “does anyone have anything to respond to this provocation?” It’s a nice way to frame what we do– when we’re questioning, or not answering a question, or making your sound soft so people listen deeper (like online participant Judy described doing for her work The Vines of Hopes and Dreams). Pervading the conference was a generous spirit of taking things apart. While the program was about sharing, it seemed like there was a lot of introspection. I think back to Emma’s intention to stop and open up a portal. That’s what Hi-Viz did with its discursive layering of different contexts. This lexicon that emerged was my provocation to think about, what does it mean to listen with one and Other?