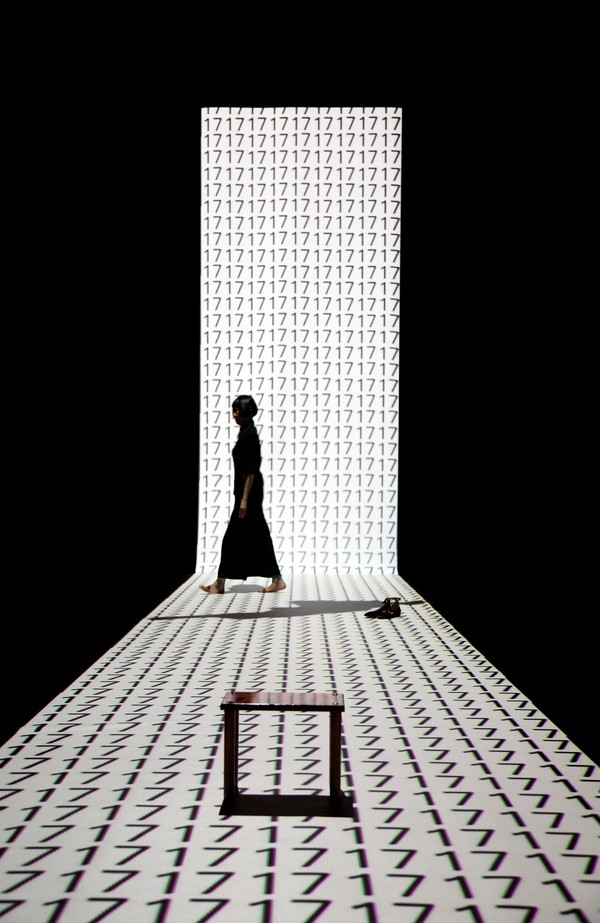

Photo: Daisy Noyes

Photo: Daisy Noyes‘All visible’: Notes from the first Hi-Viz Practice Exchange

'The quality of the time spent together is visible. The chief ingredient in rehearsal is real, personal interest.' Anne Bogart

Gian Slater reminds us that ‘ideas want to move and grow’. Later, Madeleine Flynn refers to the intuitive, private aspects of a shared creative process. Yes, I think, recognising. Those aspects can yield practical wisdom. A day-long, respectful dialogue is taking place—about overcoming isolation, and the risks of seeking to give and take skills across artforms. About making performances in unexpected situations; the wish for audiences with ‘sophisticated ears’—and a simpler wish to ‘play more’, for pleasure.1

Today is a rehearsal of sorts, for possible futures. But we’re not in a rehearsal room, feeling forced to renounce raw discoveries for our work. We’re not preoccupied by the terms of a funding agreement, and we’re not afraid of failure. Even so, during midday’s panel discussion, fear of failure is named. Without dismissal, without apology, fear of failure is declared, even, as a recurrent condition in artistic collaboration. Those around me seem to hear this with gratitude. Not for the first time, the candour on stage propels energy around the room, and I sense this on my skin. The willingness to be candid is co-created by all those who’re present, paying attention.

At The Substation in Newport, an inner suburb of Melbourne, we’re gathered to tune in and contribute to conversations among women and non-binary artists anticipated, variously, as ‘performance makers, theatre directors, composers, and sound artists’. We’re an intergenerational group of about seventy individuals who’ve signed up to partake: in food and drink; in expressions of curiosity; in interludes of knowledge sharing at large, round tables.

Lights are garlanded above. Sunshine’s bright through the paned glass, but the air temperature cool. We’re in a vast hall with many entries. Literally: this is the venue’s ‘main space’, and the doorways are seven, each over one-and-a-half metres wide. The doorways and windows opposite are framed in red—full-height drapes promote a sense of occasion.

Right now, is there more general awareness of the measurable gender disparity in Australia’s public life?2 Is there a rising mainstream interest in the lack of gender diversity and inclusion? If so, is that sustainable? ‘For a very long time’ articulate people have been seizing pens and raising their voices to point out—and resist—the lived consequences of these systemic inequalities, the ongoing impoverishment that results.3

With reference to the music industry (broadly understood), Liza Lim spoke in 2017 of ‘a continuing and gaping deficit of space’ for women.4 And in 2018, Cat Hope acknowledged the ‘lack of diversity in the opportunities for our broader community more generally’.5 So today this ‘main space’ at The Substation has symbolic meaning. In major cultural venues, the bodies of those who are marginalised are likely to be both hypervisualised and unseen. If The Substation isn’t quite a major venue on a city thoroughfare, still, for us to gather here, concentrated, making a talkative crowd at times, feels unusual. Congenial, maybe unpredictable ... exhilarating. There are elements of ceremony. Onstage and off, a riff: ‘is this a community? I hope it might be’. We’re encouraged to feel at ease, be visible to one another, and audible, and plural.

During 1995–97, visual artist Bernice McPherson was a source of inspiration for Aphids arts company (then called Aphids Events). She was interested in the hand- drawn graphic scores that were a feature of Aphids’ cross-artform projects in those early years. A mature artist and a kindred spirit, McPherson was happy to reflect aloud on her praxis, and this was formative for Aphids. She spoke to us about artists’ interdependence as a necessity that exceeds ideas about collaboration: ‘it seems to me that the development of skills and accomplishments into achievements and resolution, both personal and professional, happens during interactions with, or as a result of relationships with others’.6 Tamara Saulwick introduces this inaugural Hi-Viz Practice Exchange as ‘an experiment’. Yet it’s grounded in significant political and artistic know-how: to develop clarity, confidence, and resilience on our chosen paths we need to be present to our feedback loops of human connection: ‘there’s so much to learn’, and to learn again.

In my memory Ria Soemardjo evokes this relearning when, after a pause in her reply to a question she adds, ‘I watch that in myself’. The moment is moving, somehow. It vibrates with acceptance and encouragement that’s ‘personal, but not only personal’, as Margaret Cameron has written. Soemardjo is poised while watched and watching— and telling with exactitude (honesty).7 The next few breaths I take are slow and glad. This happens toward lunchtime; the panel discussion has become expansive (while low blood sugar, I now suspect, is another cause of lightheadedness).

***

Over plates heaped with salad, there’s nourishment of being briefly quiet, before chatting with two others about solitude ... and, with another, about writing by Ursula Le Guin. I notice afterwards I’m in a more relaxed state of receptivity, and decide to enjoy this for its own sake. My notes from the afternoon are sparse on the page, impressionistic. When I refer to them in January–February 2019, they impart a mood of more spontaneous curiosity, associative thinking.

***

Early in the day, beyond the bank of chairs, there comes about a slow dance. We’re asked how we identify ‘in terms of practice’. Emilie Collyer’s the caller. She proposes groupings and we respond, crossing the improvised dance floor, intermingling. The moves seen, of course, include a range of self-mocking gestures: an arched eyebrow, a laconic swing of arms, a turning in circles on the spot. Tamara Saulwick has already affirmed that an ‘aversion to categorising’ the work we make is understandable, ‘because this can feel reductive’.

The same may go for identifying one’s practice: how slippery and tenderising a task this can be, even when the doubter is quiet. (‘Sometimes I recall only with some effort that I’m supposed to be a poet’ is a line I treasure from Anna Kamieńska’s Notebook.8) So the considered invitation to this dance is a relief, because our identifying can be a verb that’s temporal and personal. In an interview of 2018, Jane Hirshfield was asked, ‘when did you start calling yourself a poet, and why?’. She answered, ‘I still have trouble calling myself “a poet.” The verb form is better. When I’m writing poems, I’m a poet. When I’m not writing poems, I am not’.9 Again, a relief.

Gail Priest’s keynote is titled using the gerund of the word ‘sound’, the verb from the noun. At the lectern, she speaks a ‘sounding’—an investigation—of ‘the movement of meanings’ between sound and performance (‘two modes’). She does so with reference to her many-sided career and forms of enquiry to date: initially she trained as an actor. By her own account, ‘sound is the key material of [her] communication and investigation’, but Priest’s way with words also conveys high confidence, and intensity of ideas.10

Indeed, from go we’ve been in a waltz of words—in verbal language as a key means of animating the large space, and organising participation. Meanwhile, not a few of the speakers on stage refer to ways in which verbal language acts upon their creative work, and within a collaborative process, for better, and for worse. From my notebook, here’s a sampling. On marketing: even as ‘the language is part of the content’, ‘the politics of speaking for the work’ can be hazardous. Healing ‘doesn’t happen through talking’. Around the topic of ‘new mythologies’, Adena Jacobs asks the potent question ‘what is a new language?’. Madeleine Flynn stresses the matter and mystery of ‘the lexicon’: ‘the cognitive dissonance that arises from a set of words that are shared but [turn out to] mean totally different things’.

And what about the easy violence of age-old dichotomies? The forced distinctions of genre and ‘the given’ cultural canon? No doubt an artist’s formal training influences how she conjugates her concepts and names for things. The air pops and bristles with sensitivity to words: their usage, heft, and harmony with intention. While unsurprising, this sensitivity fosters alertness. It raises a surfeit of personal questions. Also, in counterpoint, flashes of yearning for a different listening—a listening untethered by words.

Such a flash occurs when Carolyn Connors says, ‘if I am an instrument [...] I prepare my body with objects’. She recalls us to the fact that her making’s a matter of everyday neurons, sensory organs, muscles, and joints, which can gesture past the everyday. Inmost response: let’s hearken to this sounding!

Connors is reflecting on her 2018 residency in ‘the orange house by the sea’—a tranquil place where she focused on ‘voice as a place of freedom’.11 Marking the reciprocity between collaborative and solo practices, she outlines how she undertook to ask more of herself in her solo practice—a means of maturation. ‘This is a female body here, right now, at this age’, she avows. Her clarity and candour are appreciated, bracing in the best sense.

Then, as moderator of the midday panel discussion, Genevieve Lacey begins by amplifying this feeling. She leads in with thanks to Chamber Made; her dwelling on gratitude flows into a thoughtful Acknowledgement of Country through ‘the women of the Kulin nation who have been gathering on this land for so many thousands of generations [... ]’. First invoked, though, are ‘the women who have shaped our lives [... ,] those role models, those mothers, those mentors, those women whom we’ve never met but whose artworks have changed the way [...] we understand ourselves [...]. Without them, none of us could be here’.

Silently I add, ‘the many-gendered mothers of my heart’—Dana Ward’s phrase, made oft-cited and dear by Maggie Nelson in The Argonauts.12 While kindling the phrase through the poem ‘A Kentucky of Mothers’, Ward asks, ‘But is “mother of” precise? / Should I say “singers of” instead?’, stressing sound and rhythm in the unsung universe of those without whom we’d be unconvinced of the worth of our efforts, the work we create.13

‘All those women whose footsteps we walk in’. Yes. Thankyou, Genevieve Lacey. By such invocations we try to guard against the disappearance of the achievements of women and non binary artists—face down their susceptibility to erasure. Yes, again: like untold others, I take such disappearance personally. Implying risk, ‘Hi-Viz’ also connotes protection and responsibility: that of giving articulate thanks, for example.

These few months later when I’m writing, ‘Hi-Viz’ turns out to be a shorthand, too, for Anne Bogart’s resonant claim: those qualities that we cultivate—the choices we make—live in our bodies, thus in our work. Bogart’s Seven Essays on Art and Theatre offer her hardwon, direct observations about the artistic process. Among the ‘helpful notions’ in the sixth essay (pointers to discipline, really) we find, ‘your growth as an artist is not separate from your growth as a human being: it is all visible’.14 Like an overtone or harmonic, something very like this premise seemed to pulse among those present on 4 December 2018. In objective and atmosphere, a concern to nurture positive qualities was palpable. Emphasising candour and willingness, a spirit of optimism, encouragement, and gratitude, the inaugural Practice Exchange couldn’t but augur well.

Applause. The air’s warmer inside The Substation. Through the paned glass of the main space, a summer afternoon’s bright and busy. For some, trains, or children, or afterhours meetings can’t wait. We disperse as we must.

How to continue? Let’s remain farsighted, undistracted. Let’s keep re-imagining standard issue equipment to meet the challenges of our times as we desire.

Hands tingling, this body proposes, ‘shall we get back to work?’

////

* Cynthia Troup’s creative work includes scripts, stories, and podcasts. She was a founding member of Aphids. Her connection with Chamber Made began in 1994–95, when she was part of the string quartet brought together for the opera Tresno. More recent projects with Chamber Made include the Living Room Opera Turbulence (2013), for which Cynthia wrote the libretto.— see http://www.cynthiatroup.com).

1 Unless otherwise acknowledged, all quotations are from the Hi-Viz Practice Exchange; an audio document of the day’s keynote and two panel discussions can be found on this website recorded and produced by Bec Fary. Appreciative thanks to Miyuki Jokiranta for a reflective conversation in February 2019 about the event.

2 Virginia Haussegger, ‘Think We’re Doing Well on Equality? Forget It’, The Age (Melbourne),

20 December 2018, published online.

3 Liza Lim, ‘Luck, Grief, Hospitality—Rerouting Power Relationships in Music’, accessible via Lim’s website under the rubric ‘On gender disparity, structural luck and other things people have been saying for a very long time’: https://lizalimcomposer.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/1- final_lim_rerouting-power-anu-keynote.pdf. This was a keynote given at the Women and Creative Arts conference held at the Australian National University in August 2017. Warmest thanks to Liza Lim for the context yielded by a conversation in February 2019 about this keynote and related topics.

4 Lim, ‘Luck, Grief, Hospitality’, at p. 4.

5 The full transcript of Cat Hope’s 2018 Peggy Glanville Hicks Address, ‘All Music for Everyone’, was published online in Limelight Magazine, 5 December 2018, at https://www.limelightmagazine.com.au/features/limelight-in-depth-cat-hope-all-music-for-everyone/; see also https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/musicshow/cat-hope-peggy-glanville-hicks- gender-women+music/10588790.

6 Cynthia Troup, ‘Artists and Insects: Considering Collaborative Relationships’, Sounds Australian: Journal of the Australian Music Centre, no. 52 (1998), pp. 28–30 (p. 30). At https://aphids.net/about/, a paragraph of historical background precedes a list of all Aphids’ projects, from the company’s founding in 1994. In 1996, a drawing by Bernice McPherson became the basis for Travelling, a piece for solo viola composed by David Young: see https://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/product/travelling-for-solo-viola.

7 Margaret Cameron, I Shudder to Think: Performance as Philosophy (Brisbane: Ladyfinger Press, 2016), pp. 20, 21.

8 Anna Kamieńska, ‘August 8 [1972]’ from Notatnik 1965–1972, as excerpted in Polish Writers on Writing, edited by Adam Zagajewski (San Antonio TX: Trinity University Press, 2007), translated for this anthology by Alissa Valles, p. 164.

9 Palette Poetry (no interviewer named), ‘Becoming Poet: Jane Hirschfeld’ at https://www.palettepoetry.com/2018/07/06/becoming-poet-jane-hirshfield/.

10 ‘Sounding Performance: The Movement of Meanings’ is the full title of Gail Priest’s keynote; see also her ‘Brief Biography’ at http://www.gailpriest.net/bio.html.

11 For the purposes of the residency (offered by Chamber Made in 2018, and once more early in 2019), ‘the orange house by the sea’ is the name given to the home of the late Margaret Cameron: see http://chambermade.org/events/2018-ohbts-artist-residency/.

12 Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts (Minneapolis: Graywolf, 2015), p. 57, and also, for instance, p. 105. 14 Dana Ward, ‘A Kentucky of Mothers’, here published online (2014), with a brief introduction by Maggie Nelson: https://pen.org/a-kentucky-of-mothers/.

13 Anne Bogart, A Director Prepares: Seven Essays on Art and Theatre (London & New York: Routledge, 2003 edition), p. 118.